Song of the Woods

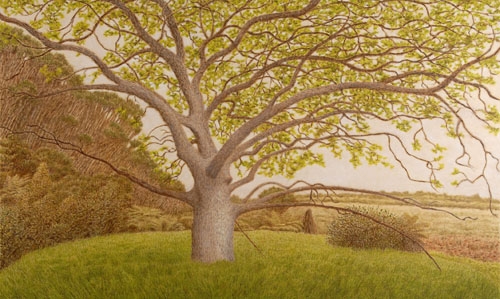

Jo Pegler – Landed

Song of the Woods

26 February – 12 June 2011

For as long as people have been producing visual imagery, the tree has been a constant. This exhibition takes its title from an unassuming photograph by an American photographer, N.S. Wooldridge, which is part of a collection of international photography acquired for the gallery by photographer Frank Denton. Many of these photographs haven’t seen the light of (in?) the gallery since their accessioning in 1925. The small selection of images that can be seen in the first bay of this exhibition is proof that this collection of photographs is one of the many facets of the gallery’s collection that has remained relatively unsung.

The analogy of the ‘woods’ can easily be applied to a collection as rich as the Sarjeant’s. There are those works that are significant and stand alone and can be viewed from many curatorial perspectives. Others are quiet, devoid of any narrative and therefore not considered; this modus operandi could relegate them to curatorial deadwood, rather than kindling. One of the challenges of any collecting institution is to try to engage these works in new conversations and bring the overlooked to light. This exhibition brings together works from the Sarjeant’s collection with new companions, some of whom may be considered uncomfortable and unlikely.

The symbolism of the tree is as ancient as human civilisation, engrained in our psyche via religion, mythology and fairytales. For some, trees are important totems inspiring worship, reverence and poetry; for others, trees simply provide the essentials of food, warmth and shelter. A screenprint by Eileen Mayo, titled The Tree, incorporates text from William Blake that sums this up: “The tree that moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way.”

Andrew McLeod’s large-scale painting Presence incorporates all we may revere and fear about the possibility of being lost in such a surreal forest. Andrea du Chatenier’s Tree of Life incorporates dismembered body parts: blackened lungs and a heart, flowers made from bone. Others, such as Bob Negrijn, Paul Johns and Johanna Pegler, depict trees as sentinels, witness to everything and nothing. The inclusion of a painting by Simon Edwards, whose work focuses on his home town of Christchurch, has taken on a new poignancy, given that many trees as well as heritage buildings are now lost as a result of the recent devastating earthquake that occurred in the city. Ann Shelton’s diptych work Landschaft – The Bridge to Nowhere, Whanganui depicts the bridge that was built in 1936 to service the ill-fated settlement of the Mangapurua Valley. Abandoned in 1942, the valley has been cloaked again in the kind of native bush that most New Zealanders hold dear as part of our ‘clean and green’ image. However, as Peter Peryer’s photograph of a hillside dotted with tree stumps on the Banks Peninsula and Richard Lyne’s painting of a stubbled logging scene attest, vast tracts of this country have been cleared of vegetation to accommodate farming and forestry.

Greg Donson

Curator/Public Programmes Manager