When is a pot more than a pot?

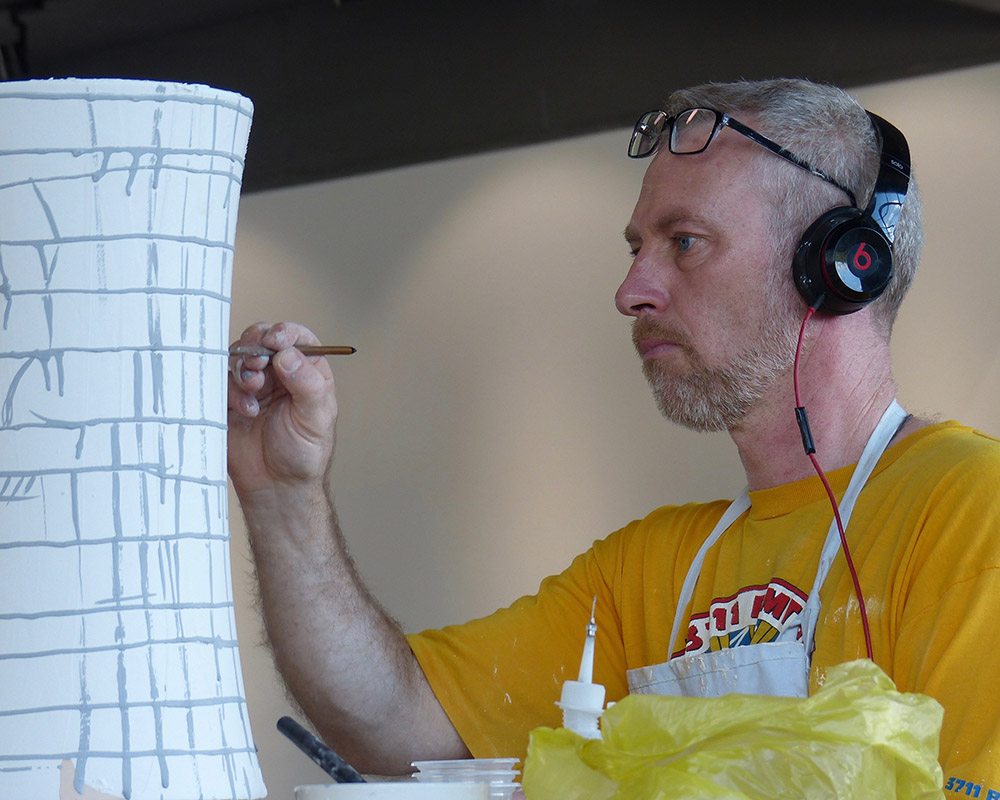

Ceramic Artist Richard Stratton

I can’t stomach much more than this is the title of a deconstructed teapot whose inner workings have been graphically displayed by its maker, ceramic artist Richard Stratton. The teapot features along with other, strangely compelling works in the exhibition Living History, on show until 11 March at the Sarjeant’s, upstairs gallery in the i-Site building. It is a presentation of work, plus new additions, created for the Dowse Art Museum, following Mr Stratton’s residency in Denmark in 2015.

This particular piece is one of several rusty looking teapots Mr Stratton made to reference, among other things, the machine age and industrialisation. He achieves the rusty or weathered look by sandblasting the lead glazes.

“I was making all these teapots, which I dissect and rebuild. I was building this one and a friend said it looks really amazing on the inside so I was wondering how you could see inside a teapot and still make it usable [the tea is held in the stomach]. That was the last one I made of that selection. Its kind of like a thing against over eating and a social commentary on consumerism and our throw away society,” Mr Stratton said.

He said he begins by doing “weird little drawings and paintings”, which trigger an idea. He then makes the clay bodies, the slips, and specialized tools to build the work. The planning and preparation done, he works solidly for three or four weeks straight, eights hours a day. One piece can take up to a month to complete.

“That’s where “I can’t stomach much more of this,” came in. It was the last in a long line of teapots.”

His work Forced Turned Teapot won the 2017 Portage Ceramic Awards Premier Prize.

Along with social and cultural history, such as the significance of tea and teapots, Mr Stratton has other strong interests that include European industrial production, the Russian Constructivist and Brutalist traditions in architecture, and early ceramic processes.

He hand makes his clay, using older clay bodies from deceased estates and a large pugmill.

“Most of them are potters’ clays that are sometimes 30 years old – clays from Kawa, and a lot of Winstone clays that aren’t available these days. When there is a potter in a family and the potter dies usually the first things to go are the kilns and the clay materials. The family asks, “What are we going to do with this huge pile of rock hard clay?” and that usually gets thrown out. So I’ve stored about two tonnes of this ancient clay from pottery sales and I don’t have to be reliant on new clay bodies.”

He uses very old recipes and has a collection of older technical books. When he was in Europe he learned skills such as slip trailing, used in the 18th century, and how to make black basalt.

“In Scandinavia I was using black clay and when I got back here there was no black clay. People keep asking for the recipe but I won’t give it because it is so toxic – there’s loads of manganese in it.”

Other pieces in the show, such as Displaced Refugee and Headpiece, are more sculptural.

“Headpiece was a strange one. Sometimes I do these works and don’t really think about what I’m doing. I just build them. I had a lot of scrap clay and just started building, and it became more of a gestural sculptural work. I’d been looking at a lot of Modernist painting and design and Brutalist buildings. I was really interested in that negative/positive play and using the colour balances. A bit like primitivism – African sculpture, which is the basis of cubism. If you blur your eyes you can see a head.”

Helen Frances