‘Leading light’: Sarjeant director feels loss of revered photographer Peter Peryer

Peter Peryer (1941 – 2018). Tahi Rua. Collection of the Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. Purchased, 1998

Peter Peryer, one of New Zealand’s foremost photographers, died suddenly on November 18, 2018, in New Plymouth. He leaves a unique legacy of photographic works in collections both around New Zealand and overseas.

“Peter was one of the leading lights of New Zealand contemporary photography – a man of humour, elegance, great personal mana, forthrightness and style; his visits to the Sarjeant were always a highlight,” says Sarjeant Gallery director, Greg Anderson.

“Peter was a proponent of photographic art and certainly the collection of his work that the Sarjeant holds reflects this. We are very proud of our long friendship and association with Peter Peryer. New Zealand has lost one of its most esteemed artists, and great characters”

The Sarjeant Gallery holds the largest collection in this country, a collection that was initiated in the 1980s by former director, Bill Milbank. The gallery holds a nationally significant collection of photographs that includes works by other acclaimed photographers such as Anne Noble, Richard Wotton and Laurence Aberhart.

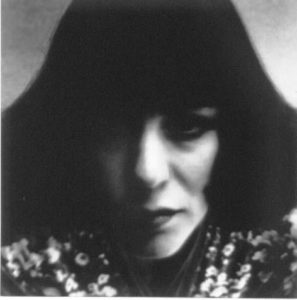

The Sarjeant’s first Peryer acquisition was Erika, 1982, a picture of his former wife.

Peter Peryer, Erika 1977 (1977) Collection of the Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. Purchased, 1978

“What interested me most about Peter was that unlike a lot of photographers at that time who started to work series on a particular subject, Peter didn’t work like that,” Milbank said.

“He photographed what he saw, and right from the very beginning was very circumspect in what he took. So often he would look at something then come back the next year and have another look before he actually took a photograph of it.

So he didn’t take lots of photos from different angles and his compositions were extremely thought through and evolved before he pressed the button. Certainly he did bracket his work to make sure he got the right exposure, [however] the time he took could be months or years. His photographs were always immediately engaging.”

Milbank noted Peryer’s strong interest in “things” in line, patterns and textures, and that the images were often very central, referencing nothing else. The photographic world of “Peryerland” also attests to a strong interest in repetition and doubles, often humorous plays on scale, and an interest in the surreal and the grotesque.

One of his early images is a Meccano toy bus struggling up a steep gradient in a rocky terrain with no horizon. A school playground map of New Zealand on concrete has been taken from an angle that suggests an aerial view of the country and a bowl of whitebait seems to be a globe.

“There is great depth in something that is quite simple and straightforward,” Milbank said.

In 1995 writer Helen Ennis noted, “The “thingness” of Peter Peryer’s subjects is respected – indeed, loved. Peryer’s world is not divided into the human and non-human, the living and the dead, the superior and inferior. The nature of the species or substances photographed is not an issue – animals, birds, people, natural and made things, all are given the same rapt attention.”

Peryer said that his works were in, one way or another, representations of himself, even his portraits of others, which express a very subjective, often moody impression of the person. An early self-portrait of Peryer holding a rooster was projected onto the wall behind the coffin at his funeral.

“He was a wonderful guy,” Milbank said. “You were always on your toes when he came through. He challenged you intellectually. He was very engaging, a very interesting person to be talking with. Like many artists he was critical of things that weren’t happening in the art world and the sorts of decisions that were being taken by certain institutions and the funding agencies.”

Peryer was a teacher and took up photography at the age of 32. He gave major solo exhibitions at the Sarjeant in 1985 and 1997 – Peter Peryer, Photographs; Second Nature and At Home and Away.

Peryer moved from Auckland to New Plymouth where he lived for around 20 years. He is survived by his son Clovis, daughter Amy, grandchildren Stan, Molly, and Rita; his siblings Natalie and Bryan; and family Erika, Jennifer, Rob, and Michiko.

By Helen Frances

This article first appeared in the Whanganui Chronicle on Tuesday 4 December 2018