Glimpses of France at the Sarjeant

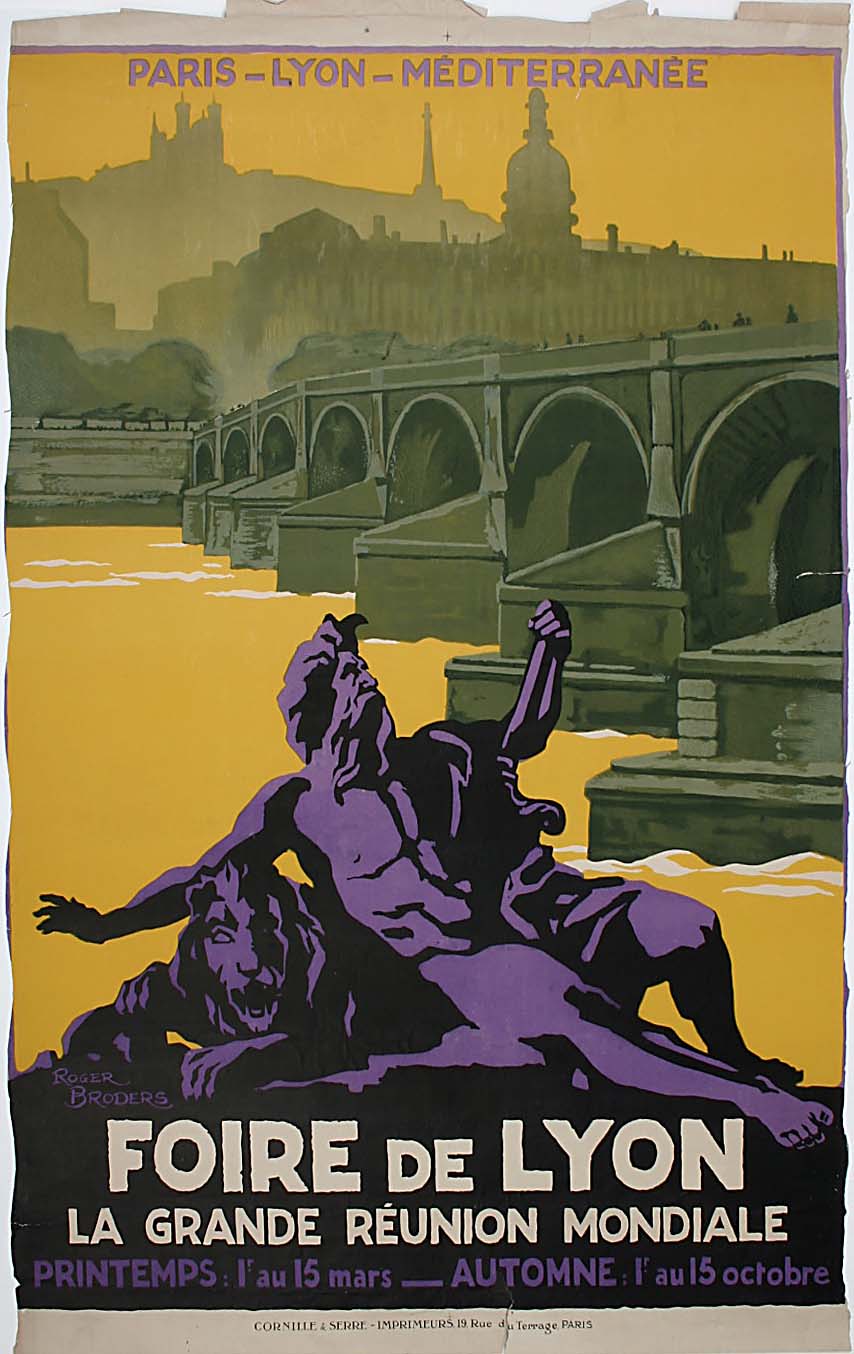

Left: Constant Léon Duval, Untitled (Château de Chenonceaux), date unknown (1910s?). Collection of Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. Right: Roger Broders, Untitled (Foire de Lyon), circa 1920.Collection of Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui

Transition project reveals glimpses of France at the Sarjeant

Traditionally found pasted to the walls of buildings and public spaces, posters have evolved throughout history as an effective medium of publicity and persuasion. Their rise to dominance as a means of mass communication began in the mid-late nineteenth century, driven largely by technological developments in the field of colour lithography.

Developed by Alois Senefelder (1771-1834), the lithographic process was first used in Munich as early as 1798. A lithograph begins its life as a drawing that is applied directly onto the print surface, traditionally a limestone block, with a greasy ink. Making use of the chemical fact that grease and water repel each other, the same surface is then dampened with water, which settles only on the unmarked areas. While the plate is still wet, a greasy printing ink is subsequently applied with a roller. Due to the presence of the water, this ink only adheres to the drawn marks. The final print is then created by running the printing surface through a press, which transfers the drawing to a piece of paper.

While the first lithographs were monochromatic, the 1830s saw commercial printers adapt the technique to produce multi-coloured images. This process was at first slow and laborious, requiring the printmaker to produce a plate for each of the desired colours. These plates were then successively printed onto a sheet of paper to create the final image. In the 1860s, Frenchman Jules Chéret (1836-1932) radically simplified this process, developing a system of producing a wide spectrum of colours with as little as three stones. Suddenly commercial printers could create colour prints more rapidly and cheaply than ever before, including posters (an art form championed by Chéret), which began to appear in great numbers in the growing cities of Europe and America in the decades that followed. During this time the poster also attracted the attention of a number of notable artists, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939), who helped to cement its status not only as an effective means of mass communication but as an independent work of art.

It was against this backdrop that major museums and art galleries around the globe began collecting posters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Sarjeant Gallery was no exception, with a collection of around 90 posters being acquired on its behalf by John and Ellen Neame around 1922 during a trip to Europe. This acquisition included a small number of large-scale posters issued by the P M L Railway to promote tourism in France. At over one metre in height, these were some of the largest works on paper that we encountered during the Transition Project.

Among the artists represented in the collection is Constant Léon Duval (1877-1956), a French painter and designer who created a large number of illustrated posters for railway companies from the 1910s until the early 1930s. A striking example of his work that is today held by the Sarjeant is a design that he produced for the Chemin de Fer D’Orléans promoting the Château de Chenonceaux in the Loire Valley, France. Placing the viewer on the banks of the River Cher in the shade of a large autumnal tree, this poster presents a beautiful, picturesque view of the east façade of the building that even now entices one to visit.

Another example from the collection is a poster designed by fellow Frenchman Roger Broders (1883-1953) promoting the Foire de Lyon, a large-scale exposition held in Lyon around 1920. In contrast to Duval’s picturesque scene, Broders does not attempt to represent a specific view of the landscape. Instead he presents the viewer with an imagined composite of elements rendered in bold colours: a man reclining on a lion (the civic symbol of Lyon), the city of Lyon itself with Fourvière Hill identifiable in the distance, and a large viaduct along which the Paris – Lyon – Méditerranée line runs, opening up the advertised event to the world.

Kimberley Stephenson

Collection Transition Assistant