07 Aug Sarjeant happenings: Sarjeant specs document reveals history of its construction

A “jolly exciting” discovery in the archives of the Whanganui Regional Museum adds new insight into the make-up of the city’s iconic Sarjeant Gallery at Pukenamu Queen’s Park.

The 1917 specification document has surfaced, full of detail for the companies who tendered for the construction of the original building.

Conservation architect Chris Cochran says it very significantly increases our knowledge of the gallery.

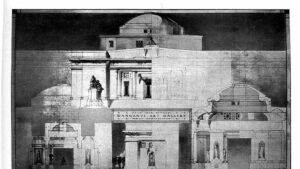

Donald Hosie’s drawing from the competition report.

The 46-page neatly typewritten document is a good example of its time.

It adds to the historical record and still has contemporary relevance.

The original building materials are described in detail, which could assist the engineers and architects working on the gallery upgrade.

We now know that the timber used in the construction of the gallery was heart rimu.

The main doors were made with mahogany veneer, while lesser doors and other joinery were of the finest grade of heart rimu.

Cochran keenly anticipated learning about the gallery floor: what timber was used and how it was built. But to his surprise, he found no answers, only intriguing questions.

The document specifies a concrete floor, covered with “Fama”. Well, what was that?

His research turned up a 1921 advertisement for this “ideal sanitary flooring for hospitals, dwelling, hotels, Etc., Etc.,” Yet the ad doesn’t actually explain what the product is.

Chris Cochran thinks it was very likely a type of linoleum that would have been patterned to give the appearance of granite or marble.

As for the substitution with timber joists and tongue-and-groove timber floorboards, “who knows when and how it came about”, he says. It’s a very important aesthetic consideration, but it may have also been driven by budget.

At the time native timbers were still readily available and so it may have been a cost-saving measure — as hard as that is to imagine now.

“It seems impossible to imagine the Sarjeant Gallery without the golden glow of its beautiful matai floors,” Sarjeant relationships officer Jaki Arthur said. “That concrete was originally specified hardly computes.”

Also absent is any reference to the clerestory windows in the ceiling. These are fully detailed in the blueprints, but it’s surprising to find no mention of the glazing, for example.

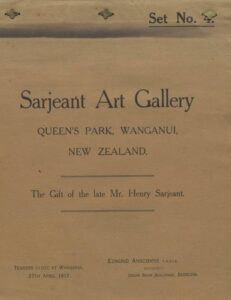

Main cover of specifications document

The clerestories fill the gallery with natural light.

While the bane of modern curators (because of the risk of UV light damaging delicate artworks) they were an innovation at the time and they were a required feature for all entries into the 1916 design competition for the Sarjeant Gallery.

There are numerous points in the specification document that sound amusing to a modern reader.

Much detail is given about the concrete, and tenderers are warned that only concrete mixers of a model approved by the architect shall be used.

Cochran was struck by a final admonishment that the building site be kept “broom clean at all times”: doubtless a thankless task assigned to the youngest apprentice.

There’s no doubt about the authorship of this document.

Although the foundation stone attributes the design of the Sarjeant Gallery to established Dunedin architect Edmund Anscombe, a close reading of the primary documents relating to the design competition makes it clear the drawings in the winning design were done after hours by an articled clerk in Anscombe’s office, Donald Hosie.

He enlisted to fight in WWI in November 1916 and was already en route to France when this document was drawn up.

The writing of the specification was a job for an experienced architect and, even if he had still been in Anscombe’s employ, Cochran thinks it unlikely Hosie would have had any input.

This latest discovery revives hope that Hosie’s original competition drawings for the Sarjeant may still survive in an archive, cupboard or attic somewhere.

The only known record is several drawings contained in a report about the competition entries. Sadly, the quality of the reproduction is very poor, but even so the beauty of the hand drawings is evident.

This article first appeared in the NZHerald online and Whanganui Chronicle on 4 August, 2020. See here