History of Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery

An excerpt from Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery: A Whanganui biography by Martin Edmond

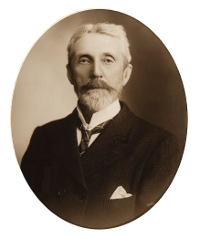

The Sarjeant Gallery was the brainchild of Henry Sarjeant and his wife Ellen, née Stewart. They were married in 1893 at Christ Church on Victoria Avenue; the wedding was the talk of the town because of the difference in their ages. He was 63 and she just 24; the eldest daughter of one of his close friends, John Tiffin Stewart, a land surveyor and engineer. Henry, a gentleman farmer, had come out from England via Australia to New Zealand in the early 1860s to join his older brother Isaac on the land. Their sister, Emma Aresti, lived in Melbourne with her lithographer husband and they moved in sophisticated art circles in that wealthy after-the-gold-rush town; Henry stayed with them before coming to Whanganui. He prospered in the new country and by the early 1890s owned 3595 acres of farmland as well as eighteen properties in the city.

The Sarjeants and the Stewarts, along with families like the Colliers, whose daughter Edith became a well-known painter, were part of a nouveau riche colonial elite who wanted Whanganui to possess the facilities of any good city — including an art gallery. Henry and Ellen shared an interest in art; for their honeymoon they took an extended tour of Europe during which they visited many galleries; and early in the new century did the same thing again. Ellen studied art at Wanganui Technical College; Henry donated money for prizes. When he died in 1912, aged 82, he left property valued at £30,000 in trust to the Wanganui Borough Council for the purpose of building and maintaining an art gallery. Ellen, who re-married and became Ellen Neame, with her second husband John was instrumental in seeing this gallery built and in assembling a collection to be housed therein. It included a three quarter size contemporary Florentine version of a Roman copy of a lost Greek sculpture called The Wrestlers.

The Neames were aided in these tasks by an able and energetic mayor, Charles Mackay, who organized a competition to find an architect to design the new gallery then drove its construction during the First World War and its immediate aftermath. The process was not without controversy. The successful design was not, it turned out, by the competition winner, Edmund Anscombe, but by Donald Hosie, one of his junior clerks. Mackay, having identified Hosie as the originator of the design, made sure he completed the working drawings for the new gallery before he went off to serve in the war. Donald Hosie was killed, along with nearly a thousand other New Zealanders, at Passchendaele on October 12, 1917. He was twenty-two years old. For many years thereafter the fiction that Anscombe designed the Sarjeant persisted.

Anscombe did supervise the building of it; and the new gallery, on Pukenamu (Sandfly Hill) overlooking the city and the river, opened, to great fanfare, in 1919. However Mackay, one of its originators, did not long survive its opening. He was a closeted gay man and this became known to his enemies, who set a honey trap for him. Mackay shot the young man who threatened to expose him, poet D’Arcy Cresswell, in the chest but did not kill him. Mackay’s subsequent fall from grace was complete; he went to jail and, upon his release, into exile. In 1929, working as a journalist in Berlin, he was himself accidentally shot dead by a policeman. Meanwhile his name was erased from the foundation stone on the building he had helped to create and his portrait removed from the council offices. Even the street in the city called after him was re-named.

Ellen and John Neame were in Europe buying art for the gallery when Mackay fell. Over the next two decades they spent more and more time overseas; in their absence Louis Cohen, Australian-born, a solicitor and a former representative cricketer, deputized for them. He was assisted in this endeavour by the appointment, in 1925, of art restorer Henry Newrick as honorary custodian and later custodian, a position he held until his death in 1950. There was no director as such; just an advisory committee and an honorary curator who was responsible for the day-to-day operation of the gallery. After Louis Cohen died suddenly, of a heart attack, in 1933, the curatorial role was given to Herbert Robertson, a medical doctor and a younger protégé of the Neames.

Ellen Neame, aged 72, died in England at the beginning of the Second World War; the council used her death as an opportunity to reassert its power by dissolving the advisory committee. Dr Robertson was in England for the duration, helping the war effort in a medical capacity; responsibility for the gallery devolved upon Charles Duigan, a stockbroker and newspaperman. When the good doctor returned in 1945, he resumed his position and kept it, implacably, until the 1970s. He was conservative, indeed reactionary, with a taste for nineteenth century English landscape painting and an inclination to exclude those he considered undesirable, like noisy children, from ‘his’ gallery. The Sarjeant Gallery’s collecting policy, innovative before the war — Louis Cohen in 1930 bought a Nugent Welch painting — was rather less vibrant thereafter.

Collection of Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. Purchased, 1930.

It was kept alive by the two custodians who followed Harry Newrick: Lawrie Major and Jim Alp. Both were artists and, while Major was not an innovator, Alp was. He installed the much-loved Mrs McSweeney, a large tabby, as the gallery’s feline in residence. He also arranged for the gallery to buy its first works by a Māori artist: two pieces commissioned in 1973 from Cliff Whiting, who was working in Whanganui as an art advisor to the Education Department. It was a sign of things to come. Dr Robertson, after forty years, saw the writing on the wall and resigned that same year. Agitation in the local arts community, advocating the appointment of a professional to run the Sarjeant Gallery along the lines of other contemporary New Zealand galleries, finally bore fruit.

Gordon Brown was the man. Appointed in 1974, he embarked upon a rigorous programme of reform aimed at adapting ‘reasonably well-established principles of art gallery management to the situation in Wanganui’. He sought to raise the profile of the gallery through exhibitions, purchases and the writing of a collection management policy; founded the Friends of the Gallery; continued to upgrade the facilities; and began assessing the extent and range of the collection. However it wasn’t long before he ran into trouble with the council and the art society, who wanted to continue to have a say in what was exhibited at the gallery and when it was exhibited. This, for sound professional reasons, was unacceptable to Brown, and he resigned after just three years in the job.

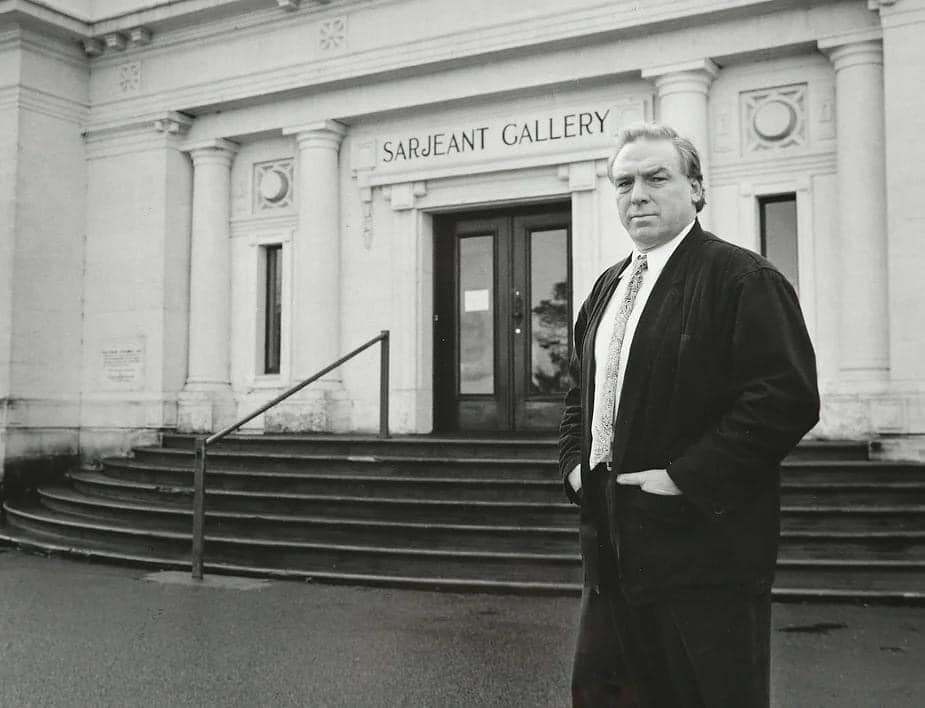

Brown appointed Deborah Maidment (later Frederikse) as registrar in 1975 (the first registrar of any art gallery in New Zealand) and she had begun to catalogue the hitherto uncatalogued collection; which, already, in the 1970s, included hundreds of works. At the same time Brown also hired Bill Milbank, who had worked previously in the town planning department at the council, as gallery assistant. When Brown resigned in 1977, Milbank was appointed acting director. He was confirmed as the second director of the Sarjeant Gallery the following year and, over the next three decades, consolidated then extended Brown’s reforms. Milbank would later describe Brown as ‘the best teacher I could ever have had.’

Milbank’s mother was a Handley, one of the old Whanganui families; he had grown up on a farm near Raetihi and gone to Ruapehu College, which had a majority of Māori students. It was clear to him that the Sarjeant Gallery should be open to Māori practitioners and he began the process of turning the gallery into a bi-cultural institution. He started collecting the work of mid-career artists like Gretchen Albrecht, Anne Noble, Peter Peryer, Matt Pine, Philip Trusttum and Mervyn Williams; and continued Brown’s policy of retrospective buying to make the collection representative in an historical sense. He also, with the help of Billy Apple, removed The Wrestlers from the centre of the gallery and in its place inaugurated an ongoing series of dome installations. And he established the gallery’s Tylee Cottage residency as a way of further enriching the local art scene.

As long ago as 1948 Edmund Anscombe identified the need for an extension to the gallery. Storage had always been a problem, as had the task of accommodating the permanent collection alongside temporary exhibits, whether drawn from the local community or from touring shows. Milbank decided, in the 1990s, to address the issue in the same way that the gallery had originally been established: by holding a competition. The winning design was by Steve McCracken of Warren and Mahoney and, after it had been chosen, attention switched to raising the funds necessary to realise it. This process was well underway — indeed it was almost complete — when, in the 2004 local body elections, Michael Laws was elected mayor on a platform which included an investigation into where the funding for the new building was coming from.

The project was mothballed. David Cairncross and all the other members of the Sarjeant Gallery Trust, which had been raising the money, resigned; Bill Milbank’s position as director was disestablished and he left the job early in 2006. The directorship remained vacant for some years afterwards. However Greg Anderson, who was appointed senior curator in 2007, was de facto director until officially confirmed in the position a decade later. The extension project remained in limbo so long as Laws was mayor; he was replaced, in 2010, by Annette Main. Chris Finlayson, Minister of Arts in the John Key National government, was instrumental in reviving the project, while Greg Anderson, ably assisted by Nicola Williams, the new chairman of the revived Trust Board, resumed fundraising for the new building.

Matters were further complicated by the forced closure of the heritage building after the Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011; a safety check showed it to be dangerously unsound. Temporary premises were found on Taupo Quay — ‘Sarjeant on the Quay’ — which operated successfully for the following ten years. Meanwhile, in addition to the money required to build the extension, funding had to be found to earthquake strengthen the heritage building. There were many vicissitudes, not to say setbacks, but in 2019 the full amount needed at that time was raised and the redevelopment project ‘green lit’. However, on the morning the first sod was to be turned, 21 March 2020, the country entered level 4 lockdown because of the covid-19 pandemic and all activity on the site ceased for a period of fifty-six days.

Work began again in May 2020 and, a little more than four years later, both the earthquake strengthened heritage building and the extension — Te Pātaka o Tā Te Atawhai Archie John Taiaroa — opened on 9 November 2024. Meanwhile, Greg Anderson departed in 2022 and his successor, Andrew Clifford, oversees the gallery as it moves confidently forward, under its fourth director, into its second century. In a fascinating development, during the earthquake strengthening a time capsule was discovered inside the walls of the heritage building. It had been placed there on 28 January 1918 by clerk of works and building supervisor John Brodie and, amongst much else, mentioned the injustice done to Donald Hosie.

That injustice has now been rectified. Further, the name of Charles Mackay has been restored (in gold lettering) to the plaque on the building he did so much to bring into being. Bill Milbank, who died in 2023, was not physically present at the opening; but his widow Raewyne Johnston was, and no doubt Bill was there in spirit; and will continue to overlook the next period of change, drama, excitement and high achievement at Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery.

He pai te tirohanga ki ngā mahara mō ngā rā pahemo engari ka puta te māramatanga i runga i te titiro whakamua. It is good to remember the past but true wisdom comes from preparing well for the future.