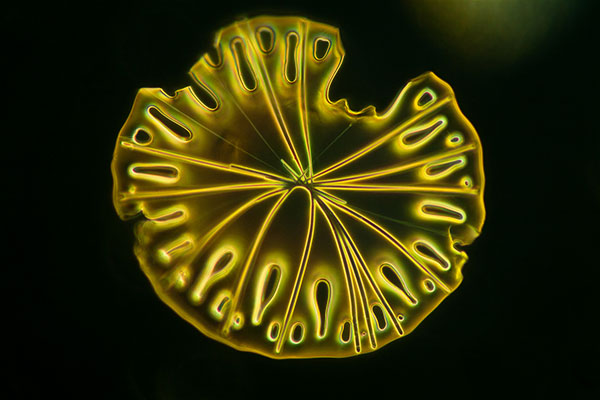

Microscopic Worlds – Wayne Barrar

Worlds, usually invisible to the naked eye, feature large on the walls of the Sarjeant Gallery as part of the current exhibition, Interior Worlds. Photographer, Wayne Barrar, brought the strangely beautiful, silica exoskeletons of diatoms out from under the microscope and the 3inch by 1inch glass slides on which they are arranged, for his project, The Glass Archive, that he has been working on since 2013. A selection was made for the show at the Sarjeant.

Mr Barrar who is an Associate Professor at Massey University’s School of Art in Wellington will give an illustrated talk about The Glass Archive project, 7.30pm, Wednesday 18 October at Sarjeant on the Quay.

While the microphotographic images of diatoms (microscopic algae) were not created specifically for the Sarjeant exhibition, Mr Barrar said there is a crossover in the idea of worlds, the link between how people see and visualise the world.

“Microscopes are a way of visualising it and photography is a way of making real that visualization or making an image of an object, and the objects here are very small and fascinating. The [diatom photographs] are as much worlds of imagination as they are of purely scientific material, so in that sense there is an interior aspect to it,” Mr Barrar said. “There is the idea of interior spaces, of interrogating and looking at the invisible magnified.”

The Glass Archive exhibition draws on material from around the world, including the renowned “Oamaru diatomite,” a sample of chalky material that dates back 35 million years. It was sent to England in the 19th century and probably came to the attention of diatomists and amateur microscopists following a display of geological deposits in 1886 at the Indian and Colonial Exhibition in London. The deposit caused a sensation on account of the rich diversity of siliceous (silica secreting) microfossil species it contained. More than 700 have been identified, single celled creatures that lived at a time when the climate was sub-tropical and the seas much warmer than they are today.

Mr Barrar has a science (BSc in Biology) and design background. He said there is a resurgence of interest in combining art with science, a connection that occurred naturally when 19th century men of leisure examined diatoms and sometimes even arranged them using a dog’s eyelash or a pig’s whisker on glass slides for scientific and recreational purposes – “it was pre-television times”.

“The wealthy were interested in both art and developments in microscope use. They would observe through microscopes and invent new ways of seeing and recording. There was a general fascination in describing the world. Diatoms were given scientific descriptions and names. They became amazing objects for scientists to study the diversity in nature. Now diatoms are still very ecologically important because they produce 25% of the world’s oxygen, and the fossil forms are used to tell us what past climates were like in relation to the species found in them.”

His diatom photographs feature mysterious blues, startling golds – against a black background. The colours are generated through the different types of lighting and photography techniques he uses.

“Because the diatoms are between glass, some have a black background; the light hits them from a certain angle so it’s a bit like having a planet in outer space where the planet is lit but all the rest of the light gets lost, so it becomes black around it. Others have quite a rich blue saturated colour caused by the filtered light I use.”

Once it is dead and under his camera on a 19th century glass slide, even didymo (slimy, brown rock snot) looks beautiful, “oddly shaped a little like a Coca Cola bottle.”

The stories associated with the diatomic world are plentiful and Mr Barrar’s talk is guaranteed to both entertain and inform.

Helen Frances